British Politics, 1793-1815:

Whigs, Tories, and Radicals

Most late-18th century politicians saw themselves as Whigs and championed the political settlement of 1688, limited monarchy, and the rule of a Protestant aristocracy. ‘Tories’, in the sense of politicians who challenged the idea of an aristocratic Protestant ascendancy, had largely ceased to exist at the national level by the time George III came to the throne.

Isaac Cruikshank, A Whig Toast - A Tory Sentement (sic), 1798, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, from here)

The impact of the French Revolution, however, deepened political division. This was also increased by the fact that, until 1801, there was a strong prime minister – Pitt – and an equally central leader of the opposition, Charles James Fox. Both men died in 1806, but their ideals (or rather, interpretations of their ideals) dominated politics until 1815 and beyond.

Fox stood against the power of the Crown and for the right of the people to express themselves through their elected MPs. His followers championed a limited degree of parliamentary reform and other measures to expand the franchise, such as abolishing the political restrictions against Catholics and non-Anglicans.

Pitt’s followers, on the other hand, were more conservative: the French Revolution suggested even mild change could be dangerous, so the existing system had to be preserved. Pitt’s followers often referred to themselves as ‘Tories’ to distinguish themselves from the Foxite Whigs.

In This Section

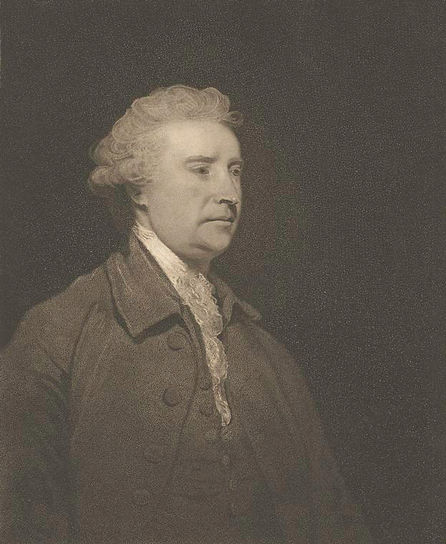

During the 1790s, Pitt enjoyed massive majorities in Parliament. This was partly because Fox’s Whigs split over the French Revolution. Fox’s friend Edmund Burke was dismayed by the possibility that radicalism and revolution might carry over to Britain from France. His Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) argued against deep-rooted change and predicted the French Revolution would devour itself.

The Duke of Portland, one of the most prominent Whigs, sympathised with Burke, and split from Fox in 1793 to form a third party before coalescing with Pitt in 1794. The Foxites were left with a rump of 40 or 50 followers, and Fox did not attend Parliament at all between 1797 and 1800.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. Edmund Burke, from here)

After Pitt’s resignation in 1801, however, the political system became confused. Pitt’s followers split over the Peace of Amiens (1802), and his former Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, joined forces with Fox in January 1804. The Foxites and Grenvilles remained in political alliance until 1817. As Pitt became disillusioned with his successor as prime minister, Henry Addington, his followers also moved into opposition. Governments were no longer able to rely on large majorities; they had to fight for their measures, and occasionally lost votes outright.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, "Confederated-Coalition; – or – The Giants storming Heaven; – with, the Gods alarmed for their everlasting – abodes", from here

A further complicating factor was the rise of popular radicalism. Popular demand for reform was driven underground during the 1790s due to government-sponsored repression, but after 1801 much of the repressive legislation was relaxed. Politicians such as Sir Francis Burdett, Lord Cochrane, and Samuel Whitbread championed radical reform in Parliament and enjoyed widespread popularity. The formation of the Friends and Advocates of Parliamentary Reform in May 1809, which included Burdett, Cochrane, and other notorious radicals, harked back to the County Association movement of the 1780s and showed that reform was returning to the national agenda.

Background image: James Fittler, The House of Commons, 1804, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, from here)